The pre-war year 1938 proved to be a defining moment for Queen Elizabeth in her role as consort to King George VI. Late 1930s Europe was clearly heading for war and the monarch needed to act as focal point for national unity. With public opinion strongly against intervention on the mainland, even in defence of allies, the need to strengthen political alliances had become vital. The royal visit to France was the occasion when Elizabeth’s natural charm combined with Norman Hartnell’s fashion to transform the public image of themonarchy. It was the perfect accompaniment to the King’s diplomatic efforts. The soft and impeccably elegant Hartnell look created, immortalised in Cecil Beaton’s famous series of photographs, was to be the hallmark of Queen Elizabeth’s style for the rest of her life. At a time of political turmoil, the State Visit was intended to reinvigorate the Entente Cordiale and to reinforce Anglo-French solidarity against Hitler’s Germany. There was a growing urgency to royal diplomacy but five days before the date of departure for Paris, Queen Elizabeth’s mother, the Countess of Strathmore, died and the visit was postponed by three weeks until 19-22 July. Hartnell was faced with a challenge: He had had to remake the Queen’s wardrobe in its entirety, substituting “many lovely colourings” with something more fitting to the period of Family Mourning. Traditional black was not a practical choice for a State Visit in the height of summer and also seemed inappropriate for the mood of the time. The couturier’s last-minute suggestion that white might be a suitable colour met with the Queen’s approval.  The delay had heightened anticipation in the French capital. The city’s mayor had asked Parisians to decorate their streets and houses with entwined colours of the two national flags. Paris was asked to show “her respectful affection for the sovereigns, her fidelity to a dear friendship and her faith in the future.” Accompanying the King, Queen Elizabeth departed Buckingham Palace in black and stepped from the Royal Train in Paris dressed in white. Among the seven Hartnell dresses in the exhibition are the crinoline worn by Queen Elizabeth to the State Banquet at the Elysée Palace and the lace dress chosen for the garden party in the Bagatelle Gardens in the Bois de Boulogne. The State Banquet was an important occasion for the King, whose speech was designed to stress shared democratic principles and Britain’s readiness to defend them.?It was a matter close to the King’s heart and he had the speech redrafted to place greater stress on the need for shared courage, wisdom and determination. The diplomat Sir Eric Phillips recorded that the State Visit had been a great success: “A manifestation of such enthusiastic warmth that by general consent, no celebration since the Armistice has evoked so profound a sense of unity, irrespective of Party and class, among the people of France.”

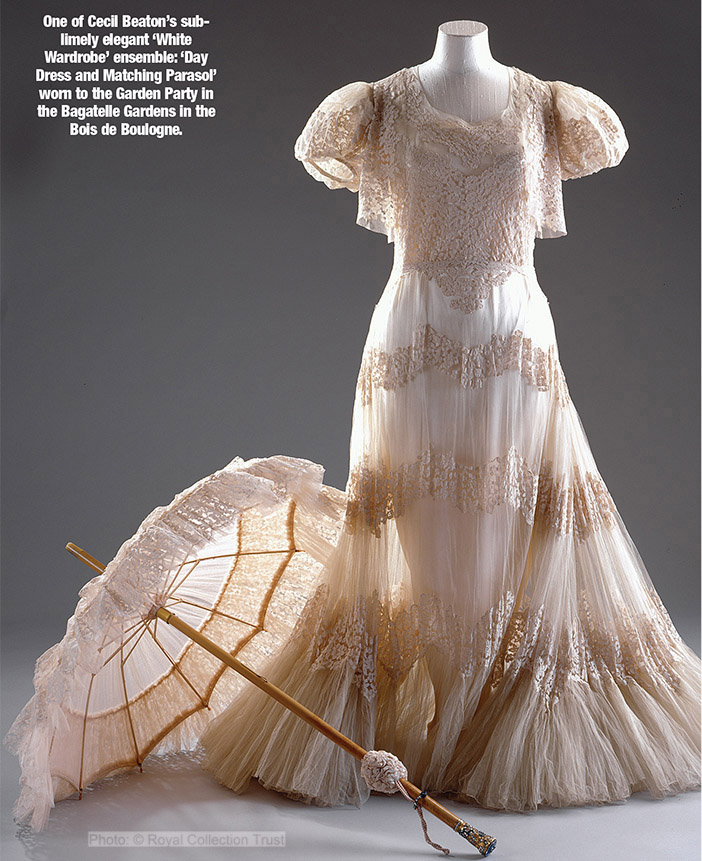

The delay had heightened anticipation in the French capital. The city’s mayor had asked Parisians to decorate their streets and houses with entwined colours of the two national flags. Paris was asked to show “her respectful affection for the sovereigns, her fidelity to a dear friendship and her faith in the future.” Accompanying the King, Queen Elizabeth departed Buckingham Palace in black and stepped from the Royal Train in Paris dressed in white. Among the seven Hartnell dresses in the exhibition are the crinoline worn by Queen Elizabeth to the State Banquet at the Elysée Palace and the lace dress chosen for the garden party in the Bagatelle Gardens in the Bois de Boulogne. The State Banquet was an important occasion for the King, whose speech was designed to stress shared democratic principles and Britain’s readiness to defend them.?It was a matter close to the King’s heart and he had the speech redrafted to place greater stress on the need for shared courage, wisdom and determination. The diplomat Sir Eric Phillips recorded that the State Visit had been a great success: “A manifestation of such enthusiastic warmth that by general consent, no celebration since the Armistice has evoked so profound a sense of unity, irrespective of Party and class, among the people of France.”  King George and Queen Elizabeth were finding their feet in these treacherous times. George was learning that he could play a significant part in international diplomacy and Elizabeth was redefining the consort’s role, bringing a vibrant immediacy and glamour to the role. In that context, Norman Hartnell’s creations have a special significance and resonance. In his memoirs he describes the daunting task of creating dresses that would be scrutinised by the fashion capital of the world. The main theme of his designs, the revival of the crinoline, was inspired by portraits in the Royal Collection, particularly those of Queen Victoria and her family by Winterhalter. The Parisians hailed Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe as a sensation; Hartnell was warmly congratulated by the leading French couturiers and made an officer of the Académie Française. The Paris autumn collections that year drew heavily on the Queen’s personal style – both the State Visit wardrobe and her Scottish ancestry – with Schiaparelli and Molyneux both incorporating plaid and tartan in their clothes. Published after the outbreak of war, Cecil Beaton’s romantic portraits of Queen Elizabeth in Hartnell’s glamourous dresses of tulles, satin, lace and silk projected an image of a confident and happy Royal Family to help uplift the nation. Beaton recalls in his diaries that the commission from Queen Elizabeth to photograph her at Buckingham Palace took him by surprise. The telephone rang: “ ‘This is the lady-in-waiting speaking. The Queen wants to know if you will photograph her tomorrow afternoon.’ At first, I thought it might be a practical joke . . . But it was no joke. My pleasure and excitement were overwhelming. In choosing me to take her photographs, the Queen made a daring innovation . . . my work was still considered revolutionary and unconventional.” (Extract from Royalty Magazine Vol. 19/11)

King George and Queen Elizabeth were finding their feet in these treacherous times. George was learning that he could play a significant part in international diplomacy and Elizabeth was redefining the consort’s role, bringing a vibrant immediacy and glamour to the role. In that context, Norman Hartnell’s creations have a special significance and resonance. In his memoirs he describes the daunting task of creating dresses that would be scrutinised by the fashion capital of the world. The main theme of his designs, the revival of the crinoline, was inspired by portraits in the Royal Collection, particularly those of Queen Victoria and her family by Winterhalter. The Parisians hailed Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe as a sensation; Hartnell was warmly congratulated by the leading French couturiers and made an officer of the Académie Française. The Paris autumn collections that year drew heavily on the Queen’s personal style – both the State Visit wardrobe and her Scottish ancestry – with Schiaparelli and Molyneux both incorporating plaid and tartan in their clothes. Published after the outbreak of war, Cecil Beaton’s romantic portraits of Queen Elizabeth in Hartnell’s glamourous dresses of tulles, satin, lace and silk projected an image of a confident and happy Royal Family to help uplift the nation. Beaton recalls in his diaries that the commission from Queen Elizabeth to photograph her at Buckingham Palace took him by surprise. The telephone rang: “ ‘This is the lady-in-waiting speaking. The Queen wants to know if you will photograph her tomorrow afternoon.’ At first, I thought it might be a practical joke . . . But it was no joke. My pleasure and excitement were overwhelming. In choosing me to take her photographs, the Queen made a daring innovation . . . my work was still considered revolutionary and unconventional.” (Extract from Royalty Magazine Vol. 19/11)